by Logan Andrew | FreeWire — Your News, Your Voice

A Fresh Approach to Growth

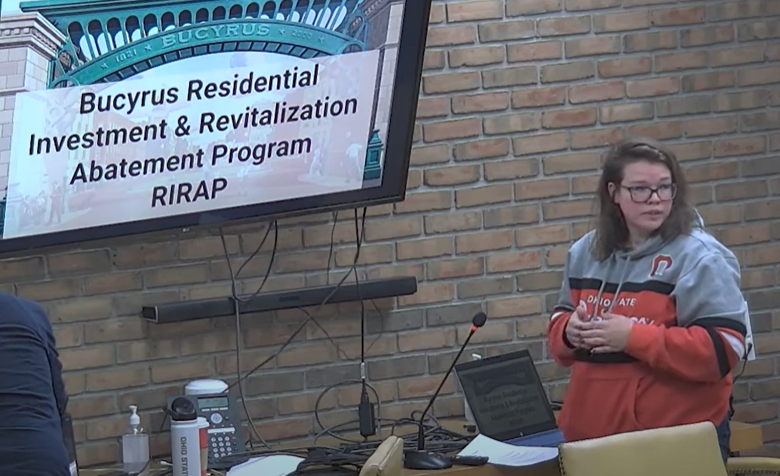

Councilmember Clarissa Slater has introduced a new plan aimed at breathing life back into Bucyrus neighborhoods. Her idea centers on tax abatements for homeowners and builders who invest in fixing up aging properties or constructing new homes on vacant lots.

Slater argues that the system discourages reinvestment. When a resident makes improvements, their property value goes up, and with it their tax bill. Her proposal attempts to break that cycle by pausing tax increases on the added value of major improvements, while still preserving the city and schools’ current revenue.

How the Plan Works

Slater’s draft is straightforward:

- Homeowners who spend at least $25,000 on big-ticket repairs—such as a roof, furnace, foundation, or plumbing—would be shielded from higher taxes on that added value for ten years.

- Building on a vacant or nearly worthless lot would earn a full five-year break, phasing into full taxation by year ten.

- In the hardest-hit neighborhoods, abatements could stretch up to fifteen years.

The program would expire after ten years unless renewed. Caps are included to prevent luxury homes from cashing in, landlords would be required to keep rents affordable, and owner-occupancy rules would stop speculators from flipping properties.

Bucyrus in Context

Bucyrus already has a citywide Community Reinvestment Area (CRA) designation dating back to 2004, which allows the city to exempt up to 100 percent of increased value for as long as fifteen years. That program is still in place and was used as recently as 2023, when the Bucyrus Storage Complex received a partial exemption.

Slater’s proposal is not meant to replace or amend the CRA. Instead, it is a separate, standalone program designed specifically for housing. While the CRA is a broad economic development tool that can apply to many types of projects, this new plan zeroes in on residential neighborhoods, vacant lots, and distressed housing stock. The goal is to offer an additional option focused solely on families and local reinvestment, operating alongside the CRA rather than in its place.

Other Ohio cities operate similar residential incentive programs. Cleveland and Columbus use tiered abatements, offering stronger incentives in struggling areas and tapering benefits in healthier ones. Cincinnati, Bowling Green, and Xenia run versions as well. These experiences show that abatements can spur private investment in weak markets, but they work best when targeted, capped, and tied to affordability.

Potential Benefits

The plan would not reduce the money currently going to schools or city services. Instead, it delays the collection of new taxes that would not exist without the improvements. The idea is that neighborhoods would stabilize as blighted homes are rehabilitated and vacant lots are developed. When abatements end, the tax base would be larger than if no improvements had taken place.

The Pushback

Council President Kurt Fankhauser has changed course since Thursday night when he expressed approval; he now criticizes the plan. In a post he wrote:

“Lord knows she’s trying. But someone needs to tell her your taxes don’t go up from replacing a furnace or doing plumbing updates. It also doesn’t go up from a new roof because the county always assumes your house has a good roof on it. This was told to me directly at the County Auditor’s office once. Doubt she has ever even paid property taxes in her life.”

There is some truth to this. Routine maintenance—such as replacing a roof, furnace, or plumbing—usually does not raise taxable value. Auditors around Ohio confirm that ordinary upkeep is already assumed in a home’s assessed value. But major renovations can and do raise values, and countywide reappraisal cycles or market sales can increase taxes even when only maintenance has been done. Fankhauser’s claim oversimplifies how assessments actually work.

As for the parting shot about whether Slater has ever paid property taxes, the ad hominem adds little to the discussion beyond personal insult. The reality is that her proposal will rise or fall on the merits, not on the contents of her tax bill.

Where the Proposal Could Be Strengthened

To maximize the benefit and avoid mistakes other cities have made, Council could refine the plan in several ways:

- Define more precisely what counts as a major repair, limiting it to structural and safety-related projects so the rules are clear.

- Set caps on the size of the benefit, or tier them based on neighborhood conditions, to prevent luxury giveaways.

- Coordinate with schools, even though abatements only delay new revenue, to keep transparency and trust.

- Enforce affordability and occupancy rules with annual certification and the ability to revoke abatements for abuse.

- Track results by publishing yearly data: permits issued, dollars invested, homes rehabilitated, and eventual tax revenue growth.

The Bigger Picture

Tax abatements are not a silver bullet. They will not single-handedly fix Bucyrus’ housing challenges or fiscal pressures. But used carefully, they can make reinvestment more attractive where private dollars have been hesitant to go.

The real test will be whether Bucyrus builds in safeguards and accountability to ensure the program benefits working families rather than serving as a windfall for developers. Done right, Slater’s proposal could help reverse decline, stabilize neighborhoods, and grow the tax base in the long run. Done poorly, it could shift burdens unfairly and miss the chance to deliver meaningful growth.

Kudos to Ms Slater for looking for solutions to a problem that exists, and putting it out there to begin a serious conversation.

Instead of belittling her, I suggest the outline she presented be given a fair consideration with adjustments to the plan so that it is tailored to the needs of Bucyrus.